Our journey to Fez started in Tangier. We’d been in Morocco a day or so, still finding our feet in the country that would be home for the next few months. After a relaxed lunch on a sunny roof terrace we got chatting with the cafe owner; a dapper fellow of a certain age, with a sports jacket and great teeth. He looked like the kind of guy who knew what was what, where to go, who to see and what to say. He also looked like he had a classic Jaguar convertible around the back, a cigarette holder and a sixties soundtrack but that’s just my imagination working a little too hard.

Looking out over the Tangier medina humming like a beehive in the noon heat, I asked him where we shouldn’t miss in Morocco. He put one arm around my shoulders and waved the other dismissively towards the old city. “Tangier?” he said, “Tourists. Marrakesh? Tourists. Casablanca? Tourists. But Fez? Ah…” He looked wistful, “Fez is the soul of Morocco”.

Tourists like us are of course often the reason why popular cities change, and sometimes become less attractive. Once we hordes arrive, some shops start catering to us over the locals, the quiet places become busy and part of the culture changes too. The ancient bakery becomes an internet cafe, the charming old road becomes a four lane highway. Many people are left better off but it’s not without its downsides. So how would the “soul of Morocco” feel now I wondered.

Fez is big – home to one and a quarter million people. But the bit most of us come to see is the old city contained by a huge wall. “There are 12,000 streets in the Medina” said the guardian at our camping area sternly. “Better to get a guide or you can become very lost”. Naturally he was able to supply a guide and a taxi to one of the Medina gates – for a significant fee. We said we would think about it.

Even though we were in Fez, it was a 10km drive to the old city. We decided to nibble the edge of it for the afternoon and walked to the main road where we hailed one of the battered red taxis. We’d braced for a battle over the price but the driver pointed to the meter (a little part of the Morocco legend falls away) and off we went, to be dropped off at the Royal Palace. There we discovered that the big doors open only for the King, along, in fact with the rest of it.

Beside the palace though, reached via alleyways running like cracks through the city is the old Jewish quarter. Fez had one of the largest populations of Jews in Morocco, established in the eighth century. The place that most of them made their home had particularly narrow streets and the buildings had their own style – many with distinctive balconies. There are hardly any Jews living there now, many departed when Israel was founded.

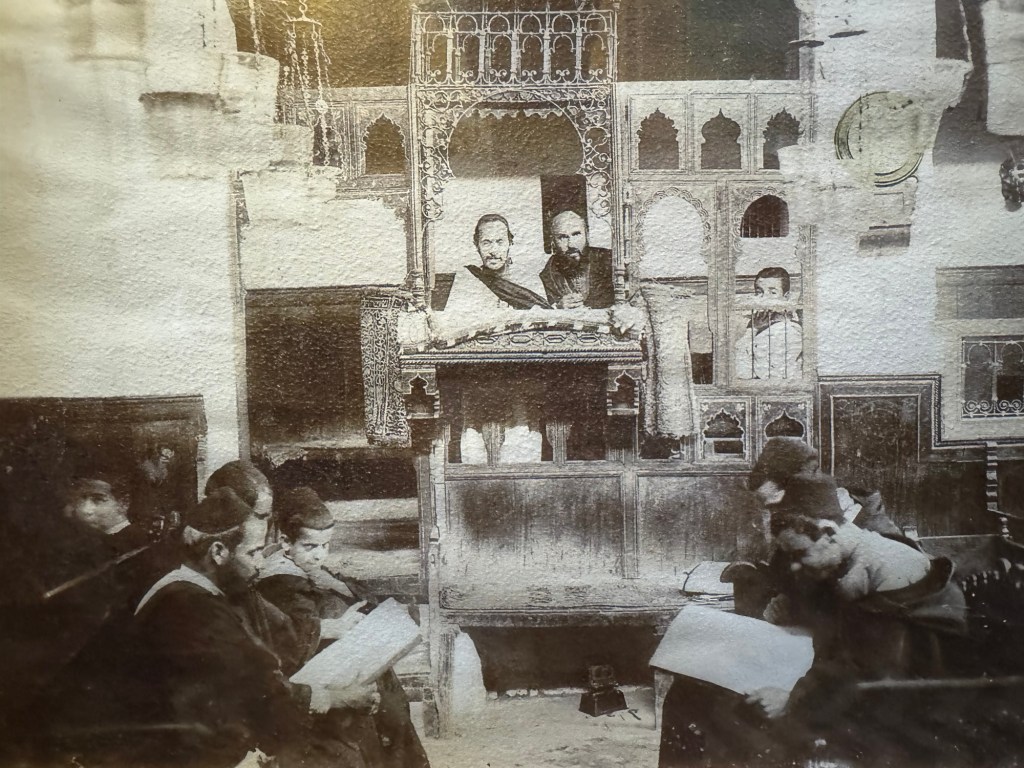

We found one of the old synagogues, rescued and restored after later life as a cow shed and a carpet warehouse. There were a couple of police officers outside – something we noticed at almost all the significant Jewish sites we passed, though none are now serving their original function. The police knocked on the door next to the synagogue entrance and a smartly dressed woman who seemed to live in the complex let us in.

She pointed out the key parts of the tall, airy space, including a tiled panel which could be lifted from the floor to reveal a women’s washing area on the lower level.

Other women would apparently lift the floor panel to see who was there. Either I couldn’t quite understand our guide’s explanation for this feature, or she didn’t quite understand it either. A Jewish guide might have been a better fit.

A vellum Torah was in its place and covered and there were one or two photos of the old synagogue in use but it felt empty and, while beautifully restored, an echo of its former self. We went up to the women’s gallery and then on to the roof where a rope of washing was hanging in the sunshine. The Jewish quarter was fascinating but without the people who’d made this neighbourhood, strangely hollow.

We walked on to find the gardens much favoured (apparently) by courting couples at sunset, but some very busy guardians were blowing whistles and clearing the place out at 5.30. So we found a bar.

That’s not something you do much of in Morocco where booze is not freely available. But there are some licensed places and we found a cracker. The top floor of “Mezzanine” had a jazzy vibe, tapas and excellent Moroccan wine. Was this a tourist thing or a Moroccan thing? Who cares. Both varieties were there and it was wonderful to watch the sky turn golden with a glass in our hands and the competing cries of the muezzins floating over the ramparts.

The next day we had to tackle the labyrinthine heart of the old city. Neither of us really wanted to spend the day with a guide. We were more interested in getting lost. So we got a cab to one of the medina gates, brushed off all offers of assistance, replied swiftly to the “Hello my friend what’s your name?” enquiries and marched on into the largest pedestrianised urban centre in the world.

The lanes were full of life and colour; rickety stalls piled high with gleaming coffee pots, clay tagines, men’s shoes, funky cushions, fluttering scarves, heady spices, shiny aubergines, leafy-topped carrots, metal tools, leather bags – anything you can think of. Cats ate food left for them next to doorways, men (always men) watched from stalls and beckoned us in, others on bikes and mopeds zipped through the crowds which parted before them and closed behind them.

Off the main thoroughfares, you quickly leave the market noise behind and enter a silent warren of deep alleyways. Some of the alleys are narrow enough that you brush both sides as you pass.

The high walls are braced apart, letting slivers of sky through. Cats lurk, children skip and adults pass wordlessly. There are mosques hidden away here too – Fez is thought to have 2-300 but no-one it seems, really knows. Dark, studded doors line every route which may end in a tunnel with another door. Then you have to remember all the turns you took to get there. Or not. While all human life – the noise and smells of Fez – surge through the shopping streets of a medina busy with tourists, there is a Fez here to which only the Moroccans really have access.

Fez also offers a quintessential Moroccan experience at the Dar Glaoui, a large complex that was almost impossible to find. It was on the map, we were in the right place but there was nothing that looked like a palace and what Google thought were alleyways to get there turned out to be dead ends. It’s seems fitting that Google can’t quite understand Fez. We eventually spotted palm trees looming over a high wall which we followed to a dark entrance.

Here was a nineteenth century palace built by the Al Glaoui family and exquisitely decorated with mosaic and tile, fountains and cool porticos. But after Moroccan independence the family fell out of favour and the palace was abandoned for decades.

Inside the portico in a gloomy corner, an old man lay in bed watching television in a haze of cigarette smoke. We asked in French if we could come in and he beckoned us over. “Vingt-cinq Dirham” he said, holding his hand out, his eyes briefly leaving the screen. We handed over the money and he waved us further into the gloom emerging in an extraordinary time capsule.

There were no guides, no leaflets, no signs, just lonely rooms to be explored. Some have collections of bric-a-brac: record players, music posters, antique cameras.

Other rooms were completely empty save for some swept rubble. In one corner a stack of antique rifles, in another a dusty tea set next to a grand velvet sofa.

Then there was the kitchen, the heart of which was a massive wood-fired range laden with pots.

This, more than anything gave me the sense of how a palace such as this would have functioned, requiring a constant stream of food preparation for the family and the staff who lived and worked there.

There were also modest displays devoted to the elderly guardian, Abdou, who turned out to be one of Morocco’s most notable modernist artists and now spends much of his days in that gloomy portico.

There were yellowing photos of him being feted in his heyday by members of the Moroccan Royal Family, celebrities and art fans.

Today there were signs of his solitary life in the palace; a trestle bed in the corner of one of the smaller rooms, a fridge and hotplate in what might have been a pantry next to the old kitchen, a friendly cat who guided us around.

I snuck around the rubble on a staircase but found the upper rooms empty. I wanted to ask how he came to be the guardian here, what he knew of the present (absentee) owners and if anyone looked after him. But he was not really interested in talking. We thanked him for allowing us in and he nodded, but when we offered our congratulations on his art, his face lit up and he looked at us more closely, eyes probing, before turning back to his tv, still smiling.

We did finally get into the park favoured by courting couples and it was lovely to see men and women mingling – as much as public sentiment allows at least. The guardians were busy with their whistles at the least hint of a smooch.

Just outside the old city we found some of the nicest food we’ve had in Morocco served by a confident young woman with excellent French and a long dark plait. It was just avocado on toast but with all sorts of seeds and spices and delicious bread. It was a modern side to Fez, rooted in tradition. We reflected on this while being bounced about in the back of a taxi going wildly fast through the glittering night, with an Arabic version of “Staying Alive” cranked up on the crackling stereo. Maybe the constant blending of old and new helps explain why Fez was in the heart of our cafe owner (and many other Moroccans we’ve spoken to). Its character is moulded by the experience and outlook of its inhabitants – modern and ancient. Like the rest of Morocco, they are such a mix; peaceful, noisy, conservative, freethinking, hustlers and scholars. Between them they’ve created the dense, vibrant layers of Fez’s history. The soul of Morocco? Quite possibly.

Leave a comment